Masjid al-Haram

| The Sacred Mosque of Mecca | |

|---|---|

Al-Masjid Al-Ḥarām (ٱَلْمَسْجِدُ ٱلْحَرَام) | |

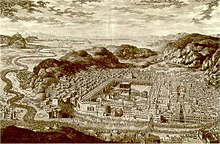

Aerial view of the mosque with the Kaaba at the center | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Branch/tradition | Muslims |

| Leadership | Abd ar-Raḥman as-Sudais (as President of the Affairs of the Two Holy Mosques and Chief Imam) Ali Ahmed Mullah (Chief Mu'athin) |

| Location | |

| Location | Mecca, Hejaz (present-day |

| Administration | General Presidency of Haramain |

| Geographic coordinates | 21°25′21″N 39°49′34″E / 21.42250°N 39.82611°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Mosque |

| Date established | 638 |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 3.0 million[2] |

| Minaret(s) | 7, (6 more under construction) |

| Minaret height | 139 m (456 ft) |

| Site area | 356,000 square metres (88 acres) [3] |

Masjid al-Haram (Arabic: ٱَلْمَسْجِدُ ٱلْحَرَام, romanized: al-Masjid al-Ḥarām, lit. 'The Sacred Mosque'),[4] also known as the Sacred Mosque or the Great Mosque of Mecca. It Is the holiest site in Islam, located in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. At its center is the Kaaba, believed by Muslims to be the first house of worship established for humankind to worship God. The mosque serves as the qibla, or direction of prayer, for Muslims globally and is the primary destination for the annual Hajj pilgrimage.

The name "Masjid al-Haram" translates to "the Sacred Mosque," a designation reflecting the prohibition of violence within its boundaries, established after the Prophet Muhammad’s entry into Mecca. Islamic tradition holds that prayers offered within this mosque are of extraordinary value, considered to be equivalent to one hundred thousand prayers offered elsewhere.

The Quran references this sacred mosque in the verse: "The first house established for humanity is the one in Bekkah—full of blessings, and guidance for humanity." (Surah Al-Imran, 3:96).

Masjid al-Haram is one of three mosques mentioned in Islamic teachings as sites for which Muslims may undertake special journeys. This principle is expressed in a hadith by the Prophet Muhammad: "Do not set out on a journey except to three mosques: this mosque of mine (the Prophet's Mosque), Masjid al-Haram, and Al-Aqsa Mosque."[5]

History

[edit]Construction of the Kaaba

[edit]Masjid al-Haram and the Kaaba begins, according to Islamic tradition, with its initial construction by angels prior to the creation of humankind. Early sources recount that this first structure was composed of a red gemstone and was later raised to the heavens at the time of the great flood. Following this event, Islamic teachings state that the Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) and his son Ismail (Ishmael) were guided to the location of the Kaaba and instructed to rebuild it. The Qur'an references this event, stating: "And ˹remember˺ when We assigned to Abraham the site of the House, ˹saying,˺ “Do not associate anything with Me ˹in worship˺ and purify My House for those who circle ˹the Ka’bah˺, stand ˹in prayer˺, and bow and prostrate themselves.'" (Surah Al-Hajj, 22:26).

Islamic tradition further narrates that the Angel Jibreel (Gabriel) presented Ibrahim with the Black Stone, which at that time was believed to be white but darkened over time due to the "sins of the children of Adam." This narrative underscores the Kaaba’s spiritual importance and its enduring role as a place of worship, purity, and historical within Islam.[6][7][8]

The Kaaba underwent a reconstruction by the Quraysh tribe in the pre-Islamic period, approximately 30 years after the Year of the Elephant. The structure required rebuilding after a fire caused by an accidental blaze, reportedly set when a Qurayshi woman was perfuming the Kaaba with incense.[9] Subsequently, the weakened structure was further damaged by flooding, prompting the Quraysh to initiate a reconstruction effort. During this period, the Prophet Muhammad, then 35 years old, participated in the rebuilding efforts alongside his uncles.[10]

When it came time to replace the Black Stone,[11] a dispute arose among the Qurayshi clans regarding who would have the honor of positioning it. To resolve the conflict, the clans agreed that the first person to enter the area would determine the placement. Muhammad was the first to arrive, and he suggested placing the Black Stone on a cloth to allow each clan leader to lift it collectively. Once raised to the appropriate height, Muhammad placed the stone in its spot.[12][13][14]

Before the Quraysh reconstruction, the first roofing of the Kaaba is attributed to Qusayy ibn Kilab, an ancestor of the Prophet Muhammad. Using Hyphaene wood and date palm fronds, Qusayy set a precedent in the architectural evolution of the Kaaba that would influence future modifications to the structure.[15]

The Mosque during the era of the Prophet Muhammad

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Since the construction of the Kaaba by the Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham), it has served as a focal point for reverence and devotion, attracting people from Mecca and beyond who took care to maintain and clothe

the sacred structure. With the advent of Islam, its sanctity was further elevated, though Muslims had limited access to pray at the Sacred Mosque before the Hijra (migration to Medina), as the Quraysh tribe generally restricted access. During this period, the Prophet Muhammad experienced the Isra and Mi'raj, the Night Journey from the Sacred Mosque to Al-Aqsa Mosque, guided by the Angel Gabriel. Tradition recounts that the Prophet began this journey while near the Hijr of the Kaaba.

In Dhu al-Qa’dah of 6 AH (628 CE), the Prophet Muhammad had a vision in which he and his followers entered the Sacred Mosque and performed the pilgrimage rites. Acting on this, he set out from Medina on the first day of Dhu al-Qa’dah, leading approximately 1,400 to 1,500 Muslims.[16] They carried only the permitted traveler’s weapons—sheathed swords—and brought 70 sacrificial animals for the pilgrimage.

Upon hearing of this, the Quraysh dispatched a force of 200 horsemen led by Khalid ibn al-Walid to intercept the group and prevent their entry to Mecca. To avoid confrontation, the Prophet took an alternate, more challenging route. He then sent Uthman ibn Affan to negotiate with the Quraysh, though Uthman’s stay in Mecca was prolonged. A rumor then spread among the Muslims that Uthman had been killed.[17] In response, the Prophet gathered his followers for the Pledge of Ridwan, a vow of loyalty and resolve to stand firm, which was taken by all but one companion, Jad ibn Qays, Allah revealed, “Certainly was Allah pleased with the believers when they pledged allegiance to you, [O Muhammad], under the tree, and He knew what was in their hearts, so He sent down tranquillity upon them and rewarded them with an imminent conquest” (Quran 48:18, Surah Al-Fath). Following this, news arrived of Uthman’s safety, prompting Quraysh to send Suhayl ibn Amr to negotiate a peace treaty, known as the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah.[18][19]

The treaty's terms allowed Muslims to return the following year to perform the Umrah pilgrimage, though they could not complete it that year. Additionally, the treaty stipulated that any Meccan joining the Muslims without Quraysh’s permission would be returned, while Muslims who defected to Mecca would not be sent back. This agreement, set to last ten years, allowed neutral tribes to ally with either side, leading the Banu Khuza'ah tribe to align with the Prophet Muhammad, while the Banu Bakr ibn Abd Manat tribe allied with Quraysh. After signing, Suhayl and his companions returned to Mecca.[20]

On the 20th of Ramadan in the eighth year of Hijra (January 10, 630 CE), the Muslims successfully conquered Mecca, an event known as the Conquest of Mecca or the "Year of the Conquest." This campaign was prompted by Quraysh’s violation of the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah when they supported the Banu Bakr tribe in an attack on the Khuza’a tribe, allies of the Muslims. In response, the Prophet Muhammad mobilized an army of 10,000 to reclaim Mecca. The Muslim forces advanced peacefully with minimal conflict, save for an isolated skirmish between Khalid ibn al-Walid’s contingent and a Qurayshi group led by Ikrima ibn Amr, resulting in twelve Qurayshi casualties and two Muslim losses.[21]

Upon entering Mecca, the Prophet went to the Kaaba, where he performed the Tawaf (circumambulation) while reciting, "And say, Truth has come, and falsehood has departed. Indeed is falsehood, [by nature], ever bound to depart" (surah Al-Isra 17:81) and “Say, The truth has come, and falsehood can neither begin [anything] nor repeat [it]’” (surah Saba 34:49). He then ordered the removal of idols and images inside and around the Kaaba.

After his circumambulation, Muhammad prayed near the well of Zamzam and drank from it, with Muslims collecting the water he touched as a blessing. Later, he led the Friday prayer at the Kaaba, where a man named Fudala ibn Amr al-Laythi, harboring ill intentions, approached him. Sensing this, Muhammad placed his hand on Fudala's chest, calming him, leading Fudala to admire him. Muhammad also instructed Bilal to give the call to prayer, witnessed by Abu Sufyan ibn Harb and others, who marveled at the loyalty he inspired. Muhammad then addressed the Meccans, revealing their private conversations, leading to the conversion of Harith and Attab.

At the time of the conquest, the Sacred Mosque (al-Masjid al-Haram) spanned approximately 1,490 square meters.[22]

During the era of the Rashidun Caliphs

[edit]

During the time of the Prophet Muhammad, the Sacred Mosque (al-Masjid al-Haram) was devoid of walls or doors, a condition that persisted throughout the caliphate of Abu Bakr as-Siddiq. In the 17th year of Hijra, under the caliphate of Umar ibn al-Khattab, the first expansion of the mosque commenced. This initiative was prompted by damage caused by the floods of Umm Nahshal, which severely affected the mosque's structures, particularly from the Sa’i area, where floodwaters inflicted extensive destruction.

Recognizing the necessity to accommodate the growing number of worshippers, Umar decided to expand the mosque. He purchased adjacent properties and integrated them into the mosque complex. Umar constructed a wall around the mosque, installed doors, and placed lamps to illuminate the area after dark. Additionally, he built a dam to redirect floodwaters away from the Kaaba and into the nearby Wadi Ibrahim. Umar ibn al-Khattab's efforts mark the first major expansion of the Sacred Mosque in the Islamic era.[23]

The Sacred Mosque (al-Masjid al-Haram) remained in its original state until the 26th year of Hijra, during the caliphate of Uthman ibn Affan, marking the beginning of the mosque's second expansion, approximately ten years after the first. Noticing the increasing population of Mecca and the growing number of pilgrims due to the rapid spread of Islam, Caliph Uthman decided to undertake the expansion of the Sacred Mosque.

The expansion began in the 26th year of Hijra and involved the purchase of adjacent properties to incorporate their land into the mosque complex. This renovation included significant enhancements to the mosque, featuring the introduction of marble columns and covered porticoes. Uthman was the first to implement these porticoes, which later became known as the "Ottoman Portico" in his honor.[24][25]

Abdullah al-Zubair's era

[edit]The third expansion of the Masjid al-Haram occurred under the rule of Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr, who undertook a reconstruction of the Kaaba following

fire damage sustained during the siege of Mecca. [26]This conflict arose from Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr’s refusal, along with his supporters in Medina, to pledge allegiance to Yazid ibn Muawiya. In response, Yazid dispatched an army under Muslim ibn Uqba, who advanced toward Mecca. After ibn Uqba’s death en route, command passed to Husayn ibn Numayr al-Sakuni, who laid siege to the city.[27][28][29]

Husayn’s forces occupied strategic positions on Mount Abu Qubays and Mount Qaʿqaʿan, bombarding Ibn al-Zubayr and his followers, who had taken refuge within the Sacred Mosque.[30][31] During the siege, fire was used, resulting in severe damage to the mosque and weakening the Kaaba’s structure. Upon Yazid's death, Husayn withdrew his forces, and Ibn al-Zubayr chose to rebuild the Kaaba completely rather than simply repair it.[32][33] He based this reconstruction on the original foundation attributed to the Prophet Abraham, building the structure to a height of 27 cubits, with walls two cubits thick, and adding two doors: an eastern entrance and a western exit.

In addition to rebuilding the Kaaba, Ibn al-Zubayr expanded the mosque itself, doubling its area to 10,000 square meters. This expansion, completed in the year 65 AH, marked as enlargement of the Masjid al-Haram to accommodate the increasing number of worshippers.[34][35]

Umayyad era

[edit]During the reign of Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf al-Thaqafi was appointed to lead a campaign against Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr, who had been resisting Umayyad rule in Mecca. Al-Hajjaj advanced on Mecca during the pilgrimage season, positioning catapults around the city.[36] Ibn al-Zubayr and his followers took refuge within the Masjid al-Haram, where the catapult bombardment caused extensive damage, including a fire that further compromised the Kaaba’s structure.[37] Ultimately, Ibn al-Zubayr was forced into open battle, where he and his remaining followers were defeated, resulting in his death.[38][39]

Upon securing Mecca, Al-Hajjaj informed Caliph Abd al-Malik that Ibn al-Zubayr had modified the Kaaba by adding an additional door.[40] Abd al-Malik instructed him to reverse these changes, restoring the structure to its original Quraysh-era design. Following the caliph’s orders, Al-Hajjaj removed six cubits of added construction, sealed the western door, and elevated the threshold of the eastern door by four cubits, installing double doors.[41]

The fourth expansion of the Masjid al-Haram took place under Caliph Al-Walid ibn Abd al-Malik in 91 AH, following severe flood damage. Al-Walid significantly enlarged the mosque, becoming the first to incorporate marble columns imported from Egypt and Syria. His renovation included marble columns and teakwood roofing with gold accents on column capitals. The inner walls were clad in marble, and mosaics adorned the arches. Al-Walid also introduced shaded canopies to protect worshippers from the sun. This expansion added approximately 2,805 square meters to the mosque’s area.[42][43]

The Abbasid era

[edit]After Al-Walid’s expansion, no major renovations of the Grand Mosque were undertaken during the remaining Umayyad period or the early Abbasid era until the reign of the second Abbasid caliph, Abu Ja'far Al-Mansur. In 137 AH, Al-Mansur ordered an extension to the mosque, expanding it north and west and doubling the increase made by Al-Walid. This expansion included the construction of a minaret at the northwest corner, the paving of the Ismail area with marble, and the installation of a protective screen over the Zamzam well.[44][45]

In 160 AH, the third Abbasid caliph, Muhammad Al-Mahdi, ordered another expansion of the mosque, extending its area further north and east.[46][47] This enlargement, however, left the Kaaba off-center within the mosque. During his second pilgrimage in 164 AH, Al-Mahdi observed this and directed an additional extension to the southern side. From Mount Abu Qubais, he examined the layout, identifying the need to reroute a stream that obstructed the southern expansion. Although Al-Mahdi passed away before its completion, his son Musa Al-Hadi finished the project in 167 AH, doubling the mosque’s area.

No further expansions occurred until 281 AH, when Caliph Al-Mu'tadid ordered repairs and modifications. He demolished Dar al-Nadwa, integrating it into the mosque’s galleries, added six large doors, and installed teak wood columns and roofing. The extension included 12 internal doors and three external ones, completed over three years.[48]

In 306 AH, Caliph Al-Muqtadir Billah incorporated two additional properties from Zubaidah bint Ja'far estate into the mosque, creating a new entrance known as Bab Ibrahim. This marked the last expansion for centuries, as subsequent Fatimid, Ayyubid, and Mamluk rulers focused solely on structural maintenance and repair.[49]

The Mamluk Sultanate Era

[edit]During the Mamluk period, the Grand Mosque underwent no major expansions; however, maintenance and renovations were conducted. In 727 AH (1327 AD), Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun allocated funds, craftsmen, and materials to repair the mosque's damaged roofs and restore several collapsed walls.[50][51] Later, in 1369 AD, Sultan Al-Ashraf Sha'ban ordered the reconstruction of the Bab al-Hazurah minaret, originally constructed by the Abbasid caliph Al-Mahdi.[52] [53][54]This minaret had collapsed due to heavy rains and was completed in 772 AH (1370 AD), with an inscription commemorating the restoration placed on a column near Bab al-Umrah.[55][56][57]

Under Sultan Faraj ibn Barquq, the Grand Mosque experienced multiple restorations.[58] In 804 AH (1402 AD), three inscriptions marked repairs initiated by his orders, particularly following a major fire in 802 AH (1399 AD) that devastated the Ramisht Lodge near Bab al-Hazurah, spreading to the mosque’s western and northern porticoes.[59][60][61] Approximately one-third of the mosque was damaged, destroying around 130 columns. Sultan Faraj ibn Barquq promptly restored these areas, addressing the extensive damage caused by the fire.[62][63][64]

In 825 AH (1421 AD), during the reign of Sultan Al-Ashraf Barsbay, the Bab al-Jana'iz was renovated with the addition of two arches, and various sections of the mosque underwent repairs. Wooden reinforcements were installed along the mosque’s sides, marked by an inscription between the arches of the Bab al-Nabi. Later, under Sultan Al-Zahir Jaqmaq’s rule, further repairs included the restoration of the Bab Ali minaret and the whitewashing of both the Bab al-Umrah and Bab al-Salam minarets. Additionally, the mosque’s roof was repaired under the supervision of Emir Sudun al-Muhammadi, reflecting the Mamluk commitment to the mosque’s structural upkeep.[65][66]

On the 16th of Shawwal in 846 AH (1442 AD), Prince Tanum, under the orders of Sultan Qaqmaq, commenced the demolition of the roof of the western portico of the Grand Mosque to continue the renovations initiated by Sudun al-Muhammadi. By the 15th of Rabi' al-Awwal in 848 AH (1444 AD), Tanum had renovated several areas within the mosque, completing the roof over the Safa side during the same year in the month of Jumada al-Awwal, and finishing the roof of the western portico. In 849 AH (1445 AD), he constructed the northern side and the adjacent western section of the sacred area, which had been damaged the previous year, under the leadership of Amir Kazaral al-Mu’allim, the Amir of the Armies in Mecca.[67][68][69][70]

In 852 AH (1448 AD), Bayram Khaja, the supervisor of the sacred precinct, renovated a section of the eastern wall of the mosque, particularly near Bab Rabat al-Sidra, and renewed seven arches in the southern portico on the northern side. An inscription, dated in Rajab of 852 AH (1448 AD), commemorating this work is preserved in the Exhibition of the Renovations of the Two Holy Mosques in Mecca.[71][72][73][74]

During the reign of Sultan Al-Ashraf Qaitbay, the Grand Mosque underwent several renovations. The first took place in 873 AH (1468 AD) when Amir Shahin began repairs from the northern side, restoring the roof with wood and plaster while also whitewashing the mosque's interior, its doors, and the three domes. In 875 AH (1470 AD), Sultan Qaitbay ordered the mosque to be paved with smooth stones, initiating further restorations and repairs, which included the Zamzam Well, the Station of Ibrahim, the Black Stone area, and other locations.[75][76][77][78]

In the reign of Sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri in 916 AH (1510 AD), the northern portico of the Grand Mosque was renovated under the supervision of the architect Khayr Bey. The following year, in 917 AH (1511 AD), Amir Khayr Bey constructed a large arch at Bab Ibrahim and completely rebuilt the area of the Black Stone (Hajar al-Ismail) using marble for both its interior and exterior. An inscription naming Sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri and previous builders was placed at the top of Hajar al-Ismail.[79][80][81][82][83]

Ottoman era

[edit]Sovereignty over the Hijaz transitioned to the Ottomans, who subsequently assumed responsibility for the two holy mosques in Mecca and Medina. The Ottoman Sultan adopted the title "Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques," signifying their commitment to the custodianship of these sacred sites. Despite the Ottomans' control over various regions, Egypt, as an Ottoman province, continued to play a pivotal role in the maintenance of the Grand Mosque, supplying funds, building materials, engineers, and labor from Egypt.[84][85]

Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent is noted as the first to undertake renovations of the Grand Mosque, having ordered repairs to the Minaret of Bab Ali after its collapse. In 959 AH (1551 AD), extensive renovations were carried out on the doors of the Grand Mosque, including the renewal of columns and porticoes, as well as the reconstruction of the maritime door and Bab Ibrahim on the western side. Additionally, the northern portico of Bab al-Nadwa was restored, and three minarets were rebuilt: the northeastern corner minaret, the Qaitbay minaret on the eastern side, and the Minaret of Bab al-Umrah.[86][87]

In 966 AH (1558 AD), Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent sent a new pulpit as a gift to the mosque, crafted from pure white marble, which replaced the previous wooden pulpit. From that time onward, the wooden pulpit was no longer utilized. In 972 AH (1564 AD), Sultan Suleiman ordered the paving of the circumambulation area (tawaf), where the tiles were sealed with lead and secured with iron nails. This paving method persisted until the entire Grand Mosque was eventually covered with plaster. A new minaret was also constructed, known as the Suleiman the Magnificent Minaret, which had previously been referred to as the Minaret of Wisdom.[88][89][90]

After Sultan Selim II ascended to the caliphate, the first renovation of the Grand Mosque took place following the decline of the Mamluk state in 979 AH (1571 AD). Sultan Selim II received reports indicating that the eastern portico's door was tilting towards the Kaaba, causing the heads of the wooden ceiling beams to protrude from their designated positions in the mosque's wall. In response, the Sultan issued orders fo

r the swift renovation of the Grand Mosque, which included renewing the roofs of the four porticoes and replacing the flat wooden ceilings with domed ceilings.[91][92][93][94][95]

Prior to the renovations under Sultan Selim II, the columns in all the porticoes adhered to a uniform architectural style. However, it became evident that this design could not adequately support the domes due to its insufficient structural integrity and inability to bear the weight of the domes requiring strong supports. Consequently, additional supports were considered to be added between the white marble columns. After Sultan Selim II's death, work continued during the reign of his son, Sultan Murad III, culminating in the completion of renovations to the southern and western sides of the mosque in 984 AH (1576 AD). The entire porticoes were whitened, and the demolition and construction process spanned four years. Following the expansions made by Selim II and Murad III, the area of the Grand Mosque increased to 28,003 square meters, transforming it into a splendid sight comparable to Iram of the Pillars, as described by the historian al-Nahrawali.[96][97][98]

During the reign of Sultan Ahmed I, cracks began to appear in the walls of the Kaaba and the surrounding structure. Sultan Ahmed contemplated demolishing the Kaaba and rebuilding it; however, Ottoman scholars advised against this course of action. Instead, engineers recommended constructing two bands of yellow copper—one above and one below—coated in gold. Despite these efforts, the Kaaba could not withstand the elements for long and collapsed during heavy rains in 1039 AH. Sultan Murad IV subsequently ordered its restoration by Egyptian engineers in 1040 AH, overseeing repairs and renovations of the entire mosque, with the ground paved with gravel. In 1045 AH (1635 AD), the mosque was further paved with small stones, and the pathways were improved. During the reign of Sultan Muhammad IV, the seven minarets were repaired and renovated, and the circumambulation area was expanded and paved with carved stones in 1072 AH (1661 AD).[99][100][101][102][103][104]

In the year 1112 AH (1700 AD), Sultan Mustafa II ordered extensive renovations of the Grand Mosque, which included repairs to its edges and the paving of pathways. The entrance at Bab al-Ziyadah and the awning above Bab al-Salam were renovated with new wood, and the minarets were restored. During the reign of Sultan Ahmed III, further renovations took place, with some areas near Bab al-Salam being paved with stone. The flooring previously laid in the mosque was removed and replaced with carved stones in 1134 AH (1721 AD).[105][106][107][108][109]

Under Sultan Abdul Hamid I, the minaret at Bab al-Umrah was repaired, and walkways were constructed using stones to facilitate the movement of pilgrims. These walkways extended from the courtyard of the mosque to Bab al-Salam, Bab Ali, Bab al-Safa, Bab Ibrahim, and Bab al-Umrah, ensuring that the passage of worshippers did not disrupt those praying in the courtyard. Additionally, some domes and the bases of columns in certain porticoes were renewed.[110][111][112][113][114]

During the reign of Sultan Mahmud II, further restoration and renovations were conducted. In 1229 AH (1814 AD), Muhammad Ali Pasha, the governor of Egypt, sent materials and resources necessary for the renovation of the Grand Mosque, including repairs to its roof. In 1257 AH (1841 AD), Sultan Abdülmecid I ordered a series of improvements to the mosque, which encompassed work on some columns and walkways, as well as an expansion of the walkway at Bab al-Safa. He also commanded the whitening of the entire Grand Mosque.[115][116]

In 1266 AH (1850 AD), Sultan Abdul Majid I issued orders for general repairs to the mosque, during which the internal corridor of Bab al-Salam was paved with marble.[117]

In 1334 AH (1915 AD), Sultan Muhammad V commanded repairs to address damages caused by the flood known as the Flood of the Khedive, which was attributed to Khedive Abbas Hilmi II, who performed the pilgrimage in 1327 AH (1909 AD), the same year the flood occurred. However, due to World War I and the onset of the Great Arab Revolt, work on the restoration of the Grand Mosque was halted.[118][119]

Saudi Arabia's Era

[edit]First Saudi expansion

[edit]The first major renovation under the Saudi kings was done between 1955 and 1973. In this renovation, four more minarets were added, the ceiling was refurnished, and the floor was replaced with artificial stone and marble. The Mas'a gallery (As-Safa and Al-Marwah) is included in the Mosque, via roofing and enclosures. During this renovation many of the historical features built by the Ottomans, particularly the support columns, were demolished.[120][121][122][123]

On 20 November 1979, the Great Mosque was seized by extremist insurgents who called for the overthrow of the Saudi dynasty. They took hostages and in the ensuing siege hundreds were killed. These events came as a shock to the Islamic world, as violence is strictly forbidden within the mosque.[124][125][126][127]

Second Saudi expansion

[edit]

The second Saudi renovations under King Fahd, added a new wing and an outdoor prayer area to the mosque. [128]The new wing, which is also for prayers, is reached through the King Fahd Gate. This extension was performed between 1982 and 1988.[129]

1987 to 2005 saw the building of more minarets, the erecting of a King's residence overlooking the mosque and more prayer area in and around the mosque itself. These developments took place simultaneously with those in Arafat, Mina and Muzdalifah. This extension also added 18 more gates, three domes corresponding in position to each gate and the installation of nearly 500 marble columns. Other modern developments added heated floors, air conditioning, escalators and a drainage system.[130][131]

In addition, the King Fahd expansion includes 6 dedicated prayer halls for people with disabilities. These halls have ramps to facilitate entry and exit with wheelchairs, as well as dedicated paths and free electric and manual carts for their use.[132][133]

Third Saudi expansion

[edit]

In 2008, the Saudi government under King Abdullah Ibn Abdulaziz announced an expansion of the mosque, involving the expropriation of land to the north and northwest of the mosque covering 300,000 m2 (3,200,000 sq ft). At that time, the mosque covered an area of 356,800 m2 (3,841,000 sq ft) including indoor and outdoor praying spaces. 40 billion riyals (US$10.6 billion) was allocated for the expansion project.

In August 2011, the government under King Abdullah announced further details of the expansion. It would cover an area of 400,000 m2 (4,300,000 sq ft) and accommodate 1.2 million worshippers, including a multi-level extension on the north side of the complex, new stairways and tunnels, a gate named after King Abdullah, and two minarets, bringing the total number of minarets to eleven. The circumambulation areas (Mataf) around the Kaaba would be expanded and all closed spaces receive air conditioning. After completion, it would raise the mosque's capacity from 770,000 to over 2.5 million worshippers. His successor, King Salman launched five megaprojects as part of the overall King Abdullah Expansion Project in July 2015, covering an area of 456,000 m2 (4,910,000 sq ft). The project was carried out by the Saudi Binladin Group. In 2012, the Abraj Al Bait complex was completed along with the 601 meter tall Makkah Royal Clock Tower.[134]

On 11 September 2015, at least 111 people died and 394 were injured when a crane collapsed onto the mosque. Construction work was suspended after the incident, and remained on hold due to financial issues during the 2010s oil glut. Development was eventually restarted two years later in September 2017.[135]

COVID-19 Pandemic

[edit]On 5 March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the mosque began to be closed at night and the Umrah pilgrimage was suspended to limit attendance. The resumption of Umrah service began on 4 October 2020 with the first phase of a gradual resumption that was limited to Saudi citizens and expatriates from within the Kingdom at a rate of 30 percent. Only 10,000 people were given Hajj visas in 2020 while 60,000 people were given visas in 2021.

The boundaries of the Holy Mosque

[edit]In his book "Akhbar Makkah," al-Azraqi states that the first person to erect boundary markers for the sacred precinct was the Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham).[136][137] Al-Azraqi narrates from Hussain ibn al-Qasim, who reported that he heard some scholars mention: "When Ibrahim said, 'O our Lord, show us our rites,' Gabriel descended to him and took him to show him the rites and pointed out the boundaries of the sacred precinct. Ibrahim began to pile stones, set up the markers, and sprinkle dust upon them, while Gabriel guided him on the limits."[138][139][140][141][142]

The markers were subsequently renewed during the time of the Prophet Muhammad. Abu Nu'aym reported from Ibn Abbas that the Prophet Muhammad sent Tamim ibn Asad al-Khuzai to renew the markers of the sacred precinct. Some accounts suggest that the Prophet Muhammad instructed Tamim ibn Asad al-Khuzai, a descendant of Abdul Rahman ibn al-Mutalib ibn Tamim, to renew them on the day of the Conquest of Makkah. The markers were further renewed during the caliphates of Umar ibn al-Khattab, Uthman ibn Affan, and Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan.[143][144][145][146][147]

The boundaries of the sacred precinct (al-Haram) are defined as follows:[148][149][150][151]

- To the North: The boundary is located near Tan'im, also known as Masjid al-Umrah, approximately 7 kilometers from the city of Medina.

- To the West: The boundary is found at al-Hudaybiyah, or al-‘Ilm, with a distance of about 18 kilometers from Jeddah.

- To the East: The boundary is situated near al-Ji'ranah, estimated to be approximately 14.5 kilometers away.

- To the South: The boundary is at Namirah, near Arafat, with a distance of about 20 kilometers from the Sacred Mosque (Masjid al-Haram).

Masjid al-Haram facilities

[edit]The facilities of the Sacred Mosque (al-Haram) are significant religious symbols located within its premises. These include:

The Kaaba (Al-Ka'bah)

[edit]

The Kaaba serves as the qibla (direction of prayer) for Muslims worldwide and is the focal point for the pilgrimage (Hajj). It is recognized as the first house established for worship on Earth and holds immense in the Islamic faith. Often referred to as the "Sacred House" (Al-Bayt al-Haram), the Kaaba is imbued with sanctity, which includes the prohibition of fighting in its vicinity, making it the holiest place on Earth for Muslims.[152][153]

Located approximately at the center of the Sacred Mosque (Al-Haram), the Kaaba is a large, elevated, cube-shaped structure measuring about 15 meters in height. The side featuring the door is 12 meters long, while the opposite side, which includes the mizab (drainage spout), measures 10 meters on each side. Originally, during the time of Ismail (Ishmael), the Kaaba stood at a height of about nine arms' lengths without a roof and had a door flush with the ground. It was later adorned with a roof by King Tubba, and then Abdul Muttalib, the grandfather of the Prophet Muhammad, added an iron door decorated with gold, marking the first time the Kaaba was embellished with gold.[154][155][156]

The Kaaba has four corners, known as:

- The Black Corner (Al-Rukn al-Aswad): The corner facing the entrance of the mosque, home to the Black Stone (Hajar al-Aswad).

- The Syrian Corner (Al-Rukn al-Shami): The corner facing Syria.

- The Yemeni Corner (Al-Rukn al-Yamani): The corner facing Yemen.

- The Iraqi Corner (Al-Rukn al-Iraqi): The corner facing Iraq.

At the top of the northern wall of the Kaaba is the mizab, made of pure gold, which overlooks the area known as Hajar al-Isma'il (the Stone of Ismail).

Hijr Ismail

[edit]The Stone of Ismail, also known as "Al-Hatim," is a part of the Kaaba. During the era of the Quraysh tribe, it was designated as "the Stone" because they left a portion of the foundation established by Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) due to their limited lawful wealth. This area was enclosed to indicate to people that it is part of the sacred Kaaba. Historical accounts suggest that during the pre-Islamic period, garments used in the rites of pilgrimage were placed in the area of the Stone, where they would remain until they deteriorated over time, thus earning the nickname "Al-Hatim." Additionally, it was a common practice for individuals to swear oaths and make covenants at this location.[157][158]

The Stone of Ismail is a semicircular structure located north of the Kaaba, aligning one end with the northern corner and the other with the western corner. It stands approximately 1.30 meters high and is traditionally regarded as the dwelling place of Ismail and his mother, Hagar. Some historical accounts even suggest that Ismail and Hagar are buried in this area.[159][160]

However, Sheikh Ibn Uthaymeen noted that the term "Stone of Ismail" may be a misnomer, as Ismail was unaware of this stone during his lifetime. The name originates from the time when the Quraysh constructed the Kaaba. Initially, the structure extended northward based on the foundations laid by Ibrahim (Abraham). When the Quraysh collected funds for the construction, their budget fell short, leading them to build only what they could afford, thus enclosing the remaining area to prevent anyone from performing tawaf (circumambulation) beyond it. Consequently, it was referred to as "the Stone" because the Quraysh enclosed it when construction was limited by their funds.[161]

Historically, the Stone has attracted interest from caliphs, kings, and princes from the Hejaz and the broader Arab and Islamic worlds. For instance, during the time of Abu Ja'far al-Mansur, the stones of the structure were exposed. After observing this during his pilgrimage, he declared, "I will not leave until the walls of the Stone are covered with marble." He promptly summoned workers to cover the stone with marble before morning, and the Abbasid caliph al-Mahdi later renewed its marble facade in 161 AH, utilizing white, green, and red marble with intricate designs.

The Stone has undergone numerous renovations throughout history. It was restored by Abu al-Abbas Abdullah ibn Dawud ibn Isa, the Amir of Mecca, in 241 AH and again during the caliphate of al-Mutawakkil in 283 AH. Further renovations were conducted by the Abbasid caliph al-Nasir in 576 AH and al-Mustansir in 631 AH, among others, including Sultan Qanṣūh al-Ghawrī in 916 AH and Sultan Abdul Majid Khan in 1260 AH (1844 CE).

In 1346 AH (1927 CE), King Abdulaziz ordered the installation of six brass chandeliers along the wall of the Stone of Ismail, each featuring three heads with an electric lamp atop each. This design remains in place today, with three lamps distributed along the semicircular structure—one at the northern corner, one at the western corner, and one at the apex of the Hatim.[162][163]

Zamzam Well

[edit]The well of Zamzam was miraculously brought forth by the angel Gabriel for Ismail and his mother, Hagar (peace be upon them), after the Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) left them in a barren valley without provisions or water. [164]As their supplies ran out, Hagar, in an act of faith and determination, searched frantically between the hills of Safa and Marwa, hoping to see any sign of help. She traversed the distance between the hills seven times before returning to her son, where she heard a voice. Calling out, “If you can help, come to my aid if you bear any good,” she was answered by Gabriel, who struck the ground, bringing forth the life-giving water of Zamzam.[165]

Hagar quickly created a makeshift barrier around the spring using sand to contain the precious water, ensuring it wouldn’t flow away before she could collect it. She drank from the well and fed her son, grateful for this divine provision. This miraculous event, recorded in Sahih al-Bukhari, marks the origins of the sacred Zamzam well, which has been a revered and relied-upon source of water for pilgrims and the people of Mecca ever since.

The Zamzam well holds a prominent place within the Masjid al-Haram and is widely revered as one of the most famous wells in the world. Its spiritual resonates deeply with Muslims, especially those undertaking Hajj and Umrah. Historically, Zamzam featured two basins: one for drinking near the Kaaba's corner and another behind it for ablution, connected by a channel for water flow. In its early form, the well had only a simple stone enclosure, lacking any substantial covering or protective grate.[166]

This changed during the Abbasid era, beginning with Caliph Abu Ja'far al-Mansur, who, in 145 AH, was the first to construct a dome over Zamzam. He also encased the well with marble and added a protective grate. Later, Caliph Muhammad al-Mahdi commissioned further renovations, and Umar ibn Faraj introduced a teakwood roof over the well area. The dome over Zamzam was adorned with mosaics, and the well chamber was renovated. In 160 AH, under al-Mahdi’s reign, the smaller dome was replaced with a larger wooden one, and the well was further enhanced with marble. Caliph al-Mu'tasim continued these enhancements, restoring the dome and marble in 220 AH, creating a well chamber that balanced both functionality and reverence.[167][168]

Maqam Ibrahim

[edit]The Station of Ibrahim, or Maqam Ibrahim, is a revered stone upon which Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) is believed to have stood during the construction of the Kaaba.[169] When the Kaaba's walls grew too high, Ibrahim used this stone as a support to continue placing stones, and it is said that his feet left a visible imprint on it.[170] Additionally, it is believed that Ibrahim stood upon this stone to proclaim the call to Hajj, inviting people to undertake the pilgrimage.[171]

The tradition of praying two units (Rak'ahs) behind the Maqam Ibrahim after Tawaf is well-established among Muslims. This act is supported by a narration from Sahih al-Bukhari, where Ibn Abbas explains, " As Abraham raises the foundations of the House, together with Ishmael, “Our Lord, accept from us; You are the Hearer, the Knower." (Surah al-Baqarah, 2:127). This ritual holds deep spiritual, linking the prayer of Muslims directly to the legacy of Prophet Ibrahim and his devotion.[172]

The Station of Ibrahim (Maqam Ibrahim) is profoundly esteemed in Islam, regarded not only as a historical relic but also as a source of spiritual blessings.[173] [174][175]A narration from al-Hakim conveys that Abdullah ibn Amr ibn al-As reported the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) said, “The Cornerstone (al-Rukn) and the Station (al-Maqam) are two gemstones from Paradise; Allah has dimmed their light, and if it were not for that, they would illuminate everything between the East and the West.”[176][177][178][179][180]

This hadith highlights the sanctity and otherworldly origin of both the Black Stone (al-Rukn) and the Station of Ibrahim. Their light has been veiled in this world to preserve the balance, yet they retain an honored place as part of the Kaaba’s heritage and its connection to the divine. Allah commanded Muslims to take the Station of Ibrahim (Maqam Ibrahim) as a place of prayer during Hajj and Umrah.[181][182]

The Abbasid Caliph al-Mahdi was the first to adorn the Maqam out of concern that it might fragment, as it is made from a soft stone. He sent a thousand dinars for reinforcement, which resulted in the station being encased with metal from top to bottom. In 236 AH, during the caliphate of al-Mutawakkil, additional gold was added above the first adornment layer.[183][184][185][186][187][188]

Safa and Marwa

[edit]

Ṣafā wal-Marwah) are two small hills, connected to the larger Abu Qubais and Qaiqan mountains, respectively, in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, now made part of Al-Masjid al-Haram. Muslims travel back and forth between them seven times in what is known as saʿī (Arabic: سَعِي, lit. 'seeking/searching or walking') ritual pilgrimages of Ḥajj and Umrah. The Sa’i begins at Al-Safa and ends at Al-Marwah, with pilgrims walking between them a total of seven times.[189][190]

Safa is a small mountain located at the bottom of the Abu Qubais Mountain, about 130 m (430 ft) southeast of the Ka'bah, which is the beginning of the Sa'ee. As for Marwa, it is also a small mountain of white stone, located 300 m (980 ft) to the northeast of the Ka'bah and it is connected to Qaiqan Mountain, marking the end of the Sa'ee.[191] Safa, Marwah and the Masa'a (space between the two mountains) were located outside the Masjid al-Haram and were separate until the year 1955/56 (1375 AH), when the project to annex the two sites into the Masjid al-Haram was undertaken for the first time, and they were subsequently annexed.[192][193]

Al-Mataf and Al-Masa'a

[edit]

The term Al-Mataf refers to the open courtyard surrounding the Kaaba within the Masjid al-Haram. [194]This area is specifically designated for the ritual of Tawaf, in which worshippers circumambulate the Kaaba in worship, as directed in Islamic teachings. During Tawaf, worshippers keep the Kaaba to their left, beginning and concluding each circuit at the Black Stone. This ritual is central to both the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages.[195]

The Mas’a, or Sa’i pathway, connects the hills of Al-Safa and Al-Marwah.[196] The practice of Sa’i commemorates Hagar’s search for water for her son, Ismail, as she traversed the distance between Al-Safa and Al-Marwah seven times. This act was later incorporated into the Hajj and Umrah rituals as a tribute to her faith and perseverance. The Prophet Muhammad also performed Sa’i during his pilgrimage, starting at Al-Safa and concluding at Al-Marwah after seven circuits.

The Mas’a is located on the eastern side of the Masjid al-Haram, measuring roughly 375 meters in length and 40 meters in width. In response to increasing pilgrim numbers, various modifications were made in the modern era. In 1925, under King Abdul Aziz’s reign, the pathway was paved with granite to minimize dust, and a roof was installed to provide shade. The doors opening onto the Mas’a were also renovated. Under King Saud, the first and second levels of the Mas’a were constructed.[197] Later, King Fahd expanded the area around Al-Safa on the first floor and introduced additional doors on the ground and first levels to improve access at Al-Marwah.[198]

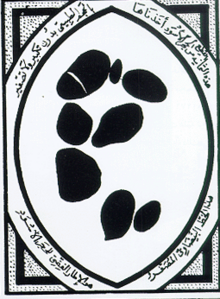

Black stone

[edit]The Black Stone (Arabic: ٱلْحَجَرُ ٱلْأَسْوَد, romanized: al-Ḥajar al-Aswad) is a rock set into the eastern corner of the Kaaba, the ancient building in the center of the Grand Mosque in Mecca, Saudi Arabia.[199] It is revered by Muslims as an Islamic relic which, according to Muslim tradition, dates back to the time of Adam and Eve.[200][201][202]

It has been narrated that Umar ibn al-Khattab would kiss the Black Stone, stating: “I know that you are just a stone that neither harms nor benefits.[203][204] If I had not seen the Messenger of Allah kissing you, I would not have kissed you.” The scholar Ibn Hajar, referencing al-Tabari, noted that Umar made this declaration because the people had recently emerged from idol worship, and he was concerned that the ignorant might perceive the act of touching the stone as a form of reverence towards stones, similar to the practices of the pre-Islamic Arabs.[205] Umar aimed to convey that touching the stone was simply an emulation of the Prophet Muhammad’s actions, rather than a belief in the stone’s inherent power to harm or benefit, as was thought concerning idols.[206][207]

Historical accounts indicate that when Muhammad ibn Abdullah was thirty-five years old (prior to his prophethood), the Quraysh sought to rebuild the Kaaba.[208] A dispute arose regarding who would have the honor of placing the Black Stone in its rightful position, nearly escalating into conflict. They ultimately agreed to accept the judgment of the first person to enter through the gate of Al-Safa. When they saw Muhammad enter first, they exclaimed, “This is the trustworthy one; we accept his judgment.” After recounting their story to him, he replied, “Bring me a garment.” When the garment was brought, he spread it out and placed the Black Stone in its center. He then instructed the leaders of each tribe to hold onto the edges of the garment, and together they carried it to the designated spot. Muhammad then took the stone and placed it in its rightful position, thus resolving the dispute.[209][210]

The Black Stone has been subjected to numerous thefts, the most notable being the incident involving the Qarmatians, who took the stone and concealed it for twenty-two years before its return in 339 AH. [211]In 317 AH, specifically on the Day of Tarwiyah, Abu Tahir al-Jannabi, the king of Bahrain and leader of the Qaramita, raided Mecca while the people were in a state of Ihram.[212] He removed the Black Stone and sent it to Hajar, resulting in the deaths of a large number of pilgrims. The Qaramita also attempted to seize the Mizab, but the tribe of Hudhayl resisted, preventing damage to the Kaaba and its Mizab. Around 318 AH, the Qaramita declared that Hajj should be performed in Al-Jash in Al-Ahsa, relocating the Black Stone to a large house. They ordered the residents of Qatif to perform Hajj at that location, but the locals refused. Consequently, the Qaramita killed many residents of Qatif, with reports indicating that the death toll in Mecca reached thirty thousand.[213]

Ibn Kathir discusses the return of the Black Stone to its original place, stating:[214]

"In the year 339 AH, in the blessed month of Dhul-Qi'dah, the Black Stone was returned to its place in the house. The Turkish prince, Bukhjam, offered the Qaramita fifty thousand dinars to return it to its original position, but they did not comply. Eventually, they sent it back to Mecca without any conditions, and it arrived in Dhul-Qi'dah of that year, all thanks and praise to Allah. The duration of its absence with them was twenty-two years, and the Muslims rejoiced greatly upon its return."[215]

Abdullah ibn al-Zubair was the first to bind the Black Stone with silver after it was damaged during the events of 64 AH, when the Kaaba was set ablaze amid the conflict between Ibn al-Zubair, who had fortified himself inside it, and the army of Yazid ibn Muawiya. This act was repeated in 73 AH by al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf al-Thaqafi. Later, the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid adorned it with diamonds and coated it in silver. In 1331 AH, Sultan Muhammad Rashad Khan gifted a frame of pure silver for the Black Stone, and in Sha'ban 1375 AH, King Saud ibn Abdulaziz placed a new silver frame around it, which was subsequently restored during the reign of King Fahd ibn Abdulaziz in 1422 AH.[216]

Construction

[edit]

Doors

[edit]In ancient times, prior to the advent of Islam and the construction of the Sacred Mosque (Masjid al-Haram), the term "doors" referred to the entrances at the ends of the paths leading to the courtyard of the Kaaba. These entrances lacked a distinct architectural form and were known as al-fujaj (narrow paths). During the Prophetic era, the doors of the Sacred Mosque retained their original names and forms as they existed in the pre-Islamic period. Among the historical accounts of the Prophet's life, some doors are mentioned by name, including the Mosque Gate (the Gate of Banu Abd Shams, also known as the Gate of Banu Shaybah or the Great Gate), the Gate of Banu Makhzum, the Gate of Banu Jumah, the Gate of Banu Sahm, and the Gate of the Hantatin (the Tailors). Some researchers estimate that there were seven doors to the mosque at that time, with two on the eastern side, three on the western side, and one on both the northern and southern sides. Certain doors acquired special during the time of Prophet Muhammad due to their connection with religious rites.[217]

During the era of Umar ibn al-Khattab, the doors took on a defined architectural form after he ordered, in 17 AH (638 CE), the enclosure of the circumambulation area (Tawaf) with a low wall. Doors were opened in alignment with the previously existing entrances between the buildings. Under Uthman ibn Affan, specifically in 26 AH (646 CE), the doors of the Sacred Mosque underwent architectural development as the mosque's area was expanded and porticoes were added, necessitating the construction of doors that included two jambs and a roofed height.

Following the era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs, the Sacred Mosque saw multiple expansions, the first being the construction by Abdullah ibn al-Zubair in 65 AH (684 CE). This expansion increased the area of the Sacred Mosque, leading to the construction of new doors to replace the old ones. Subsequent expansions occurred during the Umayyad, Abbasid, Ottoman, and modern Saudi eras, resulting in changes to the number and locations of the mosque's doors.[218]

Currently, the number of doors leading to the Sacred Mosque, including its rooftop and underground area, totals 179. These doors are made from high-quality wood and are covered with polished metal adorned with brass decorations.[219] They are equipped with digital signage that lights up green when entry is possible for worshippers and red when the mosque's capacity has been reached.

The five main doors of the Grand Mosque

[edit]- King Abdulaziz Gate: Number (1) located in the western courtyard.

- Al-Safa Gate: Number (11) located near the area of al-Safa.

- Al-Fath Gate: Number (45) located in the northern courtyard.

- Al-Umrah Gate: Number (62) located in the northern courtyard.

- King Fahd Gate: Number (79) located in the western courtyard.[220]

Among the important gates of the Masjid al-Haram:

- To the left of King Fahd Gate: (64, 70, 72, 74).

- In the eastern courtyard: (Bab al-Salam, Bab Ali, Bab al-Marwah).

- In the northern courtyard: (Bab al-Hudaybiyah, Bab al-Madina, Bab al-Quds, Bab al-Farooq).

Minarets

[edit]The construction of the first minaret in the Masjid al-Haram dates back to the Abbasid Caliph Abu Ja'far al-Mansur, who built a minaret at Bab al-Umrah during the mosque's renovation in 139 AH.[221] This minaret was renewed by the Minister of the Mosul region in 551 AH, repaired in 843 AH during the reign of Sultan Jaqmaq, and rebuilt in 931 AH under Sultan Suleiman, who topped it with a dome. Upon rebuilding, Suleiman designed its head in the style of Roman minarets.[222]

Subsequently, three additional minarets were constructed during the time of Caliph Muhammad al-Mahdi in 168 AH. One of these, located at Bab al-Salam, was two stories high and was demolished during the time of al-Nasir Faraj ibn Barquq in 810 AH. The second minaret was situated at Bab Ali and was also demolished by Sultan Suleiman, who rebuilt it using carved yellow stone and designed its head in the style of Roman minarets. The third minaret was located at Bab al-Wida (Minaret of Hazura), which was rebuilt after its collapse in 771 AH during the reign of al-Ashraf Sha'ban of Egypt. It underwent renovations the following year and was refurbished in the Ottoman style in 1072 AH, becoming known in the Ottoman era as the Minaret of Bab al-Wida.

The fifth minaret, known as the Minaret of Bab al-Ziyadah, was constructed by al-Mu'tadid Billah in 284 AH, located at Bab Dar al-Nadwa between Bab al-Ziyadah and Bab al-Qutbi. After it fell, it was rebuilt by al-Ashraf Barquq in 826 AH in the Mamluk style. A sixth minaret was constructed during the reign of Sultan Qaitbay, known as the Minaret of Qaitbay School, situated between Bab al-Nabi and Bab al-Salam. This minaret featured three stories topped with an Egyptian apex and was built in 883 AH alongside the school. Sultan Suleiman later added a seventh minaret in one of the four schools between Bab al-Salam and Bab al-Ziyadah, characterized by its height and made of yellow stone, with its head designed in the style of Roman minarets.[223]

During the Saudi era, the first expansion that began in 1375 AH involved the reconstruction of the minarets to a height of 89 meters, divided into five sections: the base, the first balcony, the shaft, the second balcony, and the cap. These were constructed in a modern style to align with the contemporary architecture of the mosque. Later, two additional minarets were added at Bab al-Fahd, bringing the total to nine. Current plans aim to add four more minarets, resulting in a total of thirteen minarets distributed across the main gates of the Masjid al-Haram, prominently featured alongside other gates and corners of the mosque.[224][225]

Minarets of the Main Entrances

[edit]- Two Minarets at Bab al-Malik Abdulaziz

- Two Minarets at Bab al-Malik Fahd

- Two Minarets at Bab al-Umrah

- Two Minarets at Bab al-Fath

- One Minaret at Bab al-Safā

Minarets of the Modern Expansion

[edit]- Two Minarets at Bab al-Malik Abdullah

- One Minaret at the Northeast Corner

- One Minaret at the Northwest Corne

General Presidency of Haramain

[edit]The General Presidency for the Affairs of the Grand Mosque and the Prophet's Mosque is a government agency directly linked to the Prime Minister of Saudi Arabia. It is responsible for the religious, administrative, technical, and service supervision of the two holy mosques and their facilities. Currently headed by Sheikh Abdul Rahman Al-Sudais, who holds the rank of Minister, the agency's headquarters is situated in Mecca, near the Grand Mosque. It also oversees a branch dedicated to the supervision of the Prophet's Mosque in Medina.

The agency was established in 1384 AH (1964 CE) under the name "General Presidency for Religious Supervision of the Grand Mosque." In 1397 AH (1977 CE), a decree transformed it into the "General Presidency for the Affairs of the Two Holy Mosques." Subsequently, in 1407 AH (1987 CE), the agency was renamed to its current title: "General Presidency for the Affairs of the Grand Mosque and the Prophet's Mosque."[226]

Al-Haram Al-Sharif Institute and College

[edit]The Holy Mosque Institute was inaugurated in 1385 AH (1965 CE) and encompasses three educational stages: intermediate, secondary, and higher education. The "Higher Department" laid the groundwork for the College of the Holy Mosque, which officially opened in 1423 AH (2002 CE), offering graduates a bachelor's degree in Islamic Law (Sharia). In 1435 AH (2014 CE), the college expanded its academic offerings by establishing departments for the study of the Qur'an and its sciences, as well as the Sunnah and its sciences. The following year, in 1436 AH (2015 CE), the Higher Department was officially renamed the College of the Holy Mosque.

Located in the King Fahd expansion of the Grand Mosque, the college provides a series of scientific circles with curricula that align with those of Sharia colleges at universities throughout the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The college employs an eight-level educational system to facilitate structured learning.[227]

Library

[edit]The Library of the Grand Mosque is one of the most libraries in Islamic history and is among the oldest libraries in the Islamic world.[228] Its establishment dates back to the second century AH (approximately the eighth century CE) during the reign of the Abbasid Caliph al-Mahdi in 160 AH.[229] The library was named the Library of the Grand Mosque by King Abdulaziz, who formed a committee of scholars from Mecca to study its status and organize it in accordance with its importance. It was officially founded in 1357 AH (1938 CE). Initially, the library's nucleus was one of the domes of the Grand Mosque, designated to preserve the Qur'ans received at the holy site. Over time, its collections expanded, leading to its relocation outside the mosque for the first time in 1375 AH, where it was affiliated with the Ministry of Hajj until 1385 AH.[230] After that, it became part of the General Presidency for Religious Supervision of the Grand Mosque, which later changed its name to the General Presidency for the Affairs of the Grand Mosque and the Prophet's Mosque. It has since evolved into a public library serving students and scholars.

The library's holdings include over half a million printed books and more than three thousand periodicals.[231] It also boasts over eight thousand original and photographic manuscripts, while the microfilm section contains over four thousand films of manuscripts. The audio library features more than forty thousand recordings of sermons and lessons from the Grand Mosque.[232] The library has moved several times: initially from a rented location in the Jarwal neighborhood following the expansion of the Grand Mosque to a new dedicated site in front of King Abdulaziz's Gate. However, subsequent expansions of the Grand Mosque led to the removal of that building, prompting another relocation to Jarwal. It was then moved to a rented space on Al-Mansour Street before finally settling in a large building in Al-Aziziyah, Mecca. The Library of the Grand Mosque also includes several private libraries that have been endowed by their owners.[233]

Kaaba Lining Factory

[edit]For centuries, the covering of the Kaaba was sent from Egypt, with only brief interruptions, until the practice was completely discontinued in 1381 AH (1961 AD). Since then, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has assumed the responsibility of producing the Kaaba's covering. The Kingdom's interest in manufacturing the covering began in 1345 AH (1926 AD) after Egypt ceased sending the covering following the notable Mahmal incident the previous year, 1344 AH (1925 AD). In response, King Abdulaziz Al Saud ordered the creation of a new covering for the Kaaba, crafted from luxurious black velvet lined with durable materials.

At the beginning of Muharram in 1346 AH (1927 AD), King Abdulaziz issued directives to establish a dedicated facility for producing the Kaaba's covering. This facility was constructed in the Al-Ajiyad neighborhood, directly across from the General Finance Ministry in Mecca. Built as a single-story structure within the first six months of 1346 AH, it became the first institution in Hijaz dedicated to weaving the Kaaba's covering since the pre-Islamic era. By the end of Dhu al-Qi'dah in 1346 AH, the new covering was completed, modeled closely after the traditional Egyptian covering with minor modifications. That year, the Kaaba was adorned with this fabric, marking the first time a covering was produced in Mecca itself.

Kaaba covering house in Al-Ajiyad continued to produce the sacred covering from its inception in 1346 AH (1927 AD) until 1358 AH (1939 AD). Following this period, the house was closed, and, after an agreement with the Saudi government, Egypt resumed the production of the Kaaba covering in Cairo. Egypt then sent the covering to Mecca annually until 1381 AH (1961 AD), when the practice ceased due to political differences between Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

In response, the Saudi government reopened an existing building affiliated with the Ministry of Finance in the Al-Jurayy area, located in front of the former Ministry of Hajj and Awqaf. This facility was tasked with managing the production of the covering, as there was no time to construct a new factory. The factory continued to produce the sacred covering until 1397 AH (1977 AD), when operations were moved to a new factory built in Umm al-Jud, Mecca. Since then, the sacred covering has been produced at this location. In 1414 AH (1994 AD), a decree was issued to integrate the factory for the Kaaba covering into the General Presidency for the Affairs of the Two Holy Mosques.[234]

Sound system

[edit]The Grand Mosque in Mecca is outfitted with around 7,500 speakers strategically positioned throughout its floors, courtyards, corridors, and adjacent streets. This vast and sophisticated audio system ranks among the largest in the world, featuring highly sensitive microphones specifically engineered to meet the mosque's extensive acoustic requirements. To ensure uninterrupted sound delivery, the system is designed to automatically switch to a backup setup in case of any primary system malfunction. Additionally, the entire audio network is connected to high-capacity UPS devices, which prevent power outages from disrupting the sound flow, enabling continuous operation until the primary system is reactivated.[235]

Accidents

[edit]On November 20, 1979, during the reign of King Khalid bin Abdulaziz, the Grand Mosque in Mecca was seized by around 200 armed insurgents who claimed the arrival of the Mahdi. Saudi forces responded by surrounding the insurgents for two weeks. On December 4, 1979, a coordinated assault successfully freed the hostages, resulting in the deaths of around 28 insurgents and injuries to approximately 17 security personnel and worshipers.[236][237]

On July 10, 1989, a double bombing struck near the Grand Mosque, with explosions on a nearby road and bridge. This attack led to one death and injuries to 16 people.[238]

On September 11, 2015, amid expansion work at the Grand Mosque, a crane collapse occurred due to severe weather conditions, including sandstorms, high winds, and heavy rain. This tragic accident took place at the beginning of the Hajj season, when large crowds were gathered. According to Saudi Civil Defense, 108 people lost their lives, and approximately 238 were injured in the incident.[239][240][241][242]

List of current and former Imams

[edit]Current Imams

[edit]- Abd ar-Rahman as-Sudais, appointed Imam and Khateeb in 1984. (Chief Imam and President of the Affairs of the Two Holy Mosques)

- Salih bin Abdullah al Humaid, appointed Imam and Khateeb in 1984. Former Chairman of Majlis Ash-Shura (Consultative Assembly of Saudi Arabia)

- Usama bin Abdullah Khayyat, appointed Imam and Khateeb in 1998.

- Mahir Al-Muayqali, appointed Imam in 2007, and Khateeb in 2016.

- Abdullah Awad Al Juhany, appointed Imam in 2007 and Khateeb in 2019.

- Faisal Jameel Ghazzawi, appointed Imam and Khateeb in 2008.

- Bandar Baleela, appointed Imam in 2013, and Khateeb in 2019.

- Yasser Al-Dosari, appointed Imam in 2015 and Khateeb in 2022.

- Al-Waleed al-Shamsan, appointed Guest Imam in Ramadan 2024, appointed permanent imam 7 months later in October 2024.

- Badr al-Turki, appointed Guest Imam in Ramadan 2024, appointed permanent imam 7 months later in October 2024.

Former Imams

[edit]- Ahmad Khatib (Arabic: أَحْمَد خَطِيْب), Islamic Scholar from Indonesia, appointed as Imam during Ottoman rule.

- Abdullah Abdul Ghani Khayat (Arabic: عبد الله عبد الغني خياط), appointed Imam and Khateeb from 1953 to 1984.

- Abdullah Al-Khulaifi (Arabic: عَبْد ٱلله ٱلْخُلَيْفِي), appointed Imam and Khateeb from 1953 until death in 1993.

- Abdullah Ibn Humaid, served as Imam from 1957 until 1981. He also served as President of Affairs of the Two Holy Mosques and as Chief Justice of Saudi Arabia.

- Mohammad Al-Subayyil (Arabic: مُحَمَّد ٱلسُّبَيِّل), served as Imam and Khateeb from 1965 to 2008. He was Chief Imam and President of the Agency for the Affairs of the Two Holy Mosques until 2008.

- Ali bin Abdullah Jaber (Arabic: عَلِى بِن عَبْدُ ٱلله جَابِر), Imam from 1981 to 1983, guest Imam for Ramadhan 1986–1989.

- Ali bin Abdur-Rahman Al-Huthaify (Arabic: عَلِي بِن عَبْدُ ٱلرَّحۡمٰن ٱلْحُذَيْفِي), guest Imam for Ramadhan 1981, 1985–1986, 1988–1991, now Chief Imam of The Prophet's Mosque.

- Umar Al-Subayyil (Arabic: عُمَر ٱلسُّبَيِّل), Imam and Khateeb from 1993 until death in 2002.

- Abdullah Al-Harazi (Arabic: عَبْد ٱلله الْحَرَازِي), former Chairman of Saudi Majlis al-Shura.

- Salah ibn Muhammad Al-Budair (Arabic: صَلَاح ابْن مُحَمَّد ٱلْبُدَيْر), led Taraweeh in Ramadan 1426 (2005) and 1427 (2006), now Deputy Chief Imam of The Prophet's Mosque.

- Adil al-Kalbani (Arabic: عَادِل ٱلْكَلْبَانِي), served as Imam for Tarawih prayers in 2008.

- Saleh Al-Talib, appointed Imam and Khatib in 2002 and served until July 2018, got imprisoned by Saudi Authorities for criticizing their actions and served 10 years in Jail

- Khalid al Ghamdi, retired as Imam and Khatib of Masjid Al Haram in September 2018, 10 years after appointment.

- Saud Al-Shuraim, appointed Imam and Khatib in 1992 and resigned in 2022.

Gallery

[edit]-

Kaaba in 1937 AD

-

Masjid al-Haram in 1907

-

Cloth of the Kaaba.

-

Prayer in the Kaaba in 1889

-

High image of the Masjid al-Haram

-

An aerial view of the area around the Makkah Mosque

-

View of the courtyard of the Grand Mosque with the Kaaba in the center

-

Masjid Al-Haram

-

Pilgrims

-

Masjid in the evening

-

Close-up of the Kaaba

-

Pilgrims on the roof of the sanctuary

-

Interior photo of the Masjid al-Haram

-

Pilgrims around Kaaba in Masjid al-Haram

-

The Kaaba

-

The Black Stone

-

Maqam Ibrahim's crystal dome

-

Mount Marwah within the mosque

-

Mount Safa

-

The well of Zamzam located beneath the floor (entrance now covered)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Location of Masjid al-Haram". Google Maps. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "AL HARAM". makkah-madinah.accor.com.

- ^ Daye, Ali (21 March 2018). "Grand Mosque Expansion Highlights Growth of Saudi Arabian Tourism Industry (6 mins)". Cornell Real Estate Review. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Denny, Frederick M. (9 August 1990). Kieckhefer, Richard; Bond, George D. (eds.). Sainthood: Its Manifestations in World Religions. University of California Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780520071896. Archived from the original on 18 September 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Narrated by al-Bukhari under No. 1189 and Muslim No. 1397, with the pronunciation of al-Bukhari.

- ^ Akhbar Mecca, Muhammad ibn Abdullah ibn Ahmad al-Azraqi, ed: Rushdi al-Salih Mulhan, Dar al-Kultura, Makkah al-Mukarramah, 2nd edition, 1416 AH/1996 AD, c. 1, p. 51: 53

- ^ I'lam al-Sajid, Muhammad bin Abdullah al-Zarkashi, ed: Sheikh Abu al-Wafa Mustafa al-Maraghi, Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, Cairo, 4th edition, 1416 AH/1996 AD, p. 45

- ^ Araf al-Tayyib, Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Aqili, investigation and study: Dr. Salahuddin Abbas Shukr, Publications of the Center for Research and Studies of Medina, 1st edition, 1428H/2007, p. 54: 71

- ^ Grand Mosque Archived December 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The Grand Mosque. Its construction and history Archived June 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Ways of guidance and guidance in the biography of the best of the best, Muhammad ibn Yusuf al-Salhi, Dar al-Kitab al-Masri, Cairo, Dar al-Kitab al-Lebanese, Beirut, 1410 AH / 1990 AD, J1, p. 181, with little adaptation.

- ^ Al-Rawd Al-Anf, Al-Suhaili, Dar Al-Fikr, Beirut, 1409 AH / 1989 AD, c. 1, p. 221.

- ^ Ways of guidance and guidance in the biography of the best of the best, Muhammad ibn Yusuf al-Salhi, Dar al-Kitab al-Masri, Cairo, Dar al-Kitab al-Lebanese, Beirut, 1410 AH / 1990 AD, J1, p. 192

- ^ Muruj al-Dhahab, al-Masudi, Dar al-Kutub al-Alamiya, Beirut, T1, 1406 AH / 1986 AD, J2, p. 295.

- ^ Mecca before Islam. Architecture and Food Archived September 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Tabaqat al-Kubra, Muhammad ibn Saad al-Baghdadi, Dar al-Sadr, Beirut, c. 2, pp. 95-105

- ^ The Prophetic Biography, Ibn Hisham, c4, pp. 275-296

- ^ Jawaama'a al-Sirah, Ali ibn Hazm al-Andalusi, realized by Ihsan Abbas and Nasser al-Din al-Asad, Dar Ihya al-Sunnah, Pakistan, 1368 AH, pp. 207-211

- ^ The Prophetic Biography, Ibn Hisham, c4 p275-296

- ^ Al-Tabqaqat al-Kubra, Muhammad ibn Saad al-Baghdadi, c2, pp. 95-105

- ^ Mentioning the reasons for marching to Makkah and mentioning the conquest of Makkah in the month of Ramadan in the year eight - The Prophetic Biography, Ibn Hisham "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-09-29. Accessed on 2013-12-23.

- ^ Islamic History, Al-Humaidi, c7, p213

- ^ Al-Azraqi's Akhbar Makkah (2:86), Al-Tabari's History (4:206).

- ^ "Uthman ibn Affan was the first to build a portico for the Grand Mosque". Makkah. December 20, 2015. Archived from the original on 2019-12-12. Accessed on 2019-09-25.

- ^ Al-Zarkashi, "Informing the Sajid on the rulings of the mosques" (p. 39).

- ^ Al-Tabari's Sahih wa Taqif al-Tabari, part 4, p. 81 + margin. Haliyyat al-'Awliya' and Tabaqat al-'Asfiya, Part 1, p. 331.

- ^ Ansab al-Ashraf, Part 4, p. 336.

- ^ Ansab al-Ashraf, Part 4, p. 340.

- ^ Akhbar Makkah, Part 1, p. 199.

- ^ Akhbar Makkah, Part 1, p. 199.

- ^ Ordeals, p. 203.

- ^ History of Khalifa, p. 252.

- ^ Al-Aghani, Part 3, p. 227.

- ^ Quoted from History of the Sacred Mosque, p. 17 by Baslamah

- ^ Al-Azraqi's Akhbar Makkah (2:69-71)

- ^ Syed Amir Ali, A Brief History of the Arabs, p. 81.

- ^ Hamdi Shaheen, The Defamed Umayyad State, p. 349.

- ^ Nabih Aqeel, History of Bani Umayyah, p. 107.

- ^ Ibn al-Athir, Al-Kamil in History, Vol. IV, p. 309.

- ^ The reason for the demolition of the Kaaba after Islam Archived August 31, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Quoted from the History of the Sacred Mosque, p. 19, and Sir Al-Alam Al-Nablaa (5:48).

- ^ News of Mecca (2:17).

- ^ The Story of the Great Expansion, p. 193.

- ^ Manahat al-Karam by Al-Sinjari, 2/90.

- ^ Architecture of the Grand Mosque throughout Islamic history Archived June 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ News of Makkah by Al-Azraqi: 2/74

- ^ Makkah news for Fakhi: 2/165.

- ^ Akhbar al-Karam with the news of the Sacred Mosque by Ahmad al-Makki: P. 184.

- ^ Informing the learned scholars about the construction of the Grand Mosque by Abd al-Karim bin Moheb al-Din al-Qutbi: 2/366.

- ^ Ibn Fahd, Kitab Ithaf al-Warra, C3, p. 185

- ^ Ibn Fahd, Kitab Ithaf al-Warra, C3, p. 187

- ^ Al-Fassi, Chefaa Al-Gharam Book, C1, p. 204

- ^ Al-Fassi, Shifa'a Al-Ghoram Book, C1, p. 238

- ^ Qutb al-Din al-Hanafi, Qutbi's History, p. 351

- ^ Ibn Fahd, Kitab Ithaf al-Warra, C3, p. 312

- ^ Ibn Fahd, Kitab Ithaf al-Warra, C3, pp. 311-312

- ^ Al-Fassi, Chefaa Al-Gharam Book, C1, p. 240

- ^ Al-Fassi, Shifa'a Al-Ghoram Book, C1, p. 106

- ^ Al-Sabbagh, The Book of Achievement. Manuscript p. 83

- ^ Abu al-Tayyib al-Makki, Kitab al-Zuhur al-Muqtatifa from Makkah, manuscript. P38

- ^ Qutb al-Din al-Hanafi, History of the Holy Land, p. 83

- ^ Ahmad Zaini Dahlan, Kitab al-Kalam, p. 128

- ^ Muhammad al-Faar, The Evolution of Writings and Inscriptions in the Hejaz, p. 284

- ^ Muhammad al-Faar, The Evolution of Writings and Inscriptions in the Hejaz, p. 70

- ^ Al-Azraqi, Akhbar Makkah c2 p93

- ^ Islamah, Book of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque, p. 183

- ^ Ibrahim Rifaat Pasha, The Mirror of the Two Haramain, p. 240

- ^ Al-Fassi, Shifaa Al-Gharam C1, p. 239

- ^ Ibn Dhahir al-Qurashi, Kitab al-Jami al-Latif, p. 217

- ^ Al-Nahrawali, Kitab al-Alam (Book of Flags), C3, p. 207

- ^ Qutb al-Din al-Hanafi, The History of Qutbi, p. 183

- ^ Ahmad Nafaa, The Book of the Conditions of the Two Holy Mosques. Manuscript. Pg. 26

- ^ Al-Sabbagh, The Book of Achievement. Manuscript p. 84

- ^ Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani, The Book of the Sons of Al-Ghamr. C3 p536

- ^ Islamah, The History of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque, p. 265

- ^ Al-Jaziri, Drar al-Fadhir al-Fadhida al-Organized, p. 25

- ^ Ibn Fahd, Ittihaf al-Warra, C4, p. 212

- ^ Ahmad Zaini Dahlan, Kitab al-Kalam, p. 134

- ^ Qutb al-Din al-Nahrawani, Kitab al-Alam al-Alam al-Bayt al-Haram, p. 240.

- ^ Ahmad Nafaa, The Book of the Conditions of the Two Holy Mosques. Manuscript. Pg. 37

- ^ Al-Sinjari, Manahat Al-Karm, C2, p. 19

- ^ Al-Nahrawali, Kitab al-Alam (Book of Flags), C3, p. 244

- ^ Al-Kurdi, The Book of Righteous History, C3, p119

- ^ Egypt's cladding of the Kaaba is an honor throughout history that we did not receive Archived February 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Amal Essien, The Historical Journal, manuscript, p. 3

- ^ Islamah, The History of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque, p. 78

- ^ Al-Dahlan, The Book of the Summary of Words, p. 41

- ^ Abdul Majeed Bakr, The Book of the Most Famous Mosques of Islam, C1, p. 22

- ^ Dahlan, Khalqat al-Kalam, p. 40

- ^ Amal Essien, Moroccan Historical Review, No. 31/32, manuscript, p. 4

- ^ Ali Muhyiddin, Kitab al-Arj al-Miski fi al-Tarikh al-Makki, manuscript, p. 69

- ^ Al-Tabari, Ittihaf Fadlat al-Zaman, manuscript, p. 252

- ^ Qutb al-Din al-Hanafi, Kitab Tariq al-Qutbi, p. 224

- ^ Islamah, The History of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque, p. 83

- ^ Al-Nahrawali, Kitab al-I'lam al-Alam al-Baytullah al-Haram, C3, p. 394

- ^ Islamah, The History of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque, p. 87

- ^ Tawfiq Abdel Gawad, The History of Medieval and Euro-Islamic Architecture, C2, p. 254

- ^ Islamah, The History of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque, p. 89

- ^ Al-Tabari, Ittihaf al-Fadlat al-Zaman, manuscript, p. 193

- ^ Al-Sinjari, Manahat al-Karm, c. 3, p. 145

- ^ Dahlan, History of Islamic States, p. 128

- ^ Al-Asadi, Akhbar al-Karam, Akhbar al-Masjid al-Haram, pp. 118-119

- ^ Muhammad Salih al-Shibi al-Abdari, Kitab al-Alam al-Anam on the History of the House of God, manuscript, p. 27

- ^ Al-Sinjari, Manahat al-Karm, c3, p184-185

- ^ Al-Kurdi, Al-Qawim History of Mecca and the Holy House of Allah, C3, pp. 231-232

- ^ Al-Sinjari, Manahat al-Karm, p. 221

- ^ Al-Azraqi, Supplement to Akhbar Makkah, p. 372

- ^ Al-Sabbagh, Kitab Tahdhib al-Maram, manuscript, p. 94

- ^ Islamah, History of the Architecture of the Sacred Mosque, p. 271

- ^ Islamah, The History of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque, p. 272

- ^ Islamah, The History of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque, p. 272

- ^ Al-Sabbagh, Tajmul al-Maram in Akhbar al-Bayt al-Haram, manuscript, p. 95

- ^ Ahmed Al-Sebai, History of Mecca, p. 592

- ^ Islamah, The History of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque, p. 185

- ^ National Archives, Cairo, Abdeen Governorate, Portfolio No. 250 Abdeen, Arabic disclosure copy No. 456, dated 17 Dhu al-Qa'dah 1250 AH/1834 AD

- ^ Islamah, The History of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque, p. 272

- ^ Islamah, The History of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque, p. 254

- ^ Islamah, The History of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque, p. 277

- ^ Fawzia Hussein Matar, margin of the History of the Architecture of the Grand Mosque from the Second Abbasid Era to the Ottoman Era, p. 264

- ^ Al Jazeera - On the anniversary of National Day Archived August 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Architecture of the Grand Mosque in the Saudi era Archived February 03, 2018, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Uncle Muallem Muhammad Awad bin Laden Archived February 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Islamic Solidarity Magazine (formerly Hajj Magazine), 44th year, Part IX, Rabiul Awwal (1410 AH/October 1989 AD), pp. 58-60.

- ^ The efforts of the Saudi Arabian government in expanding the Two Holy Mosques and serving pilgrims and pilgrims Archived March 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ https://www.kapl-hajj.org/mosque_expansion_.php Archived September 02, 2017, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Al-Qafla Magazine, Volume 47, Issue 10, Shawwal 1419 AH, p. 61